Do attackers really attack printers?

Emily and Michael put a printer honeypot on the Internet to see who would attack it and how. It didn’t turn out as expected! Our honeypot experiment suggests exposed printers are not a target for cyber-attacks.

Background

Printers are a potential attack vector to get onto a network. Modern printers support a wide variety of features and can include storing documents on the printer, authenticating users, integrating with Active Directory, and accessing network storage using stored credentials. Further, many printers run on embedded operating systems and amount to mini-servers.

When a printer is exposed to the Internet, the features pose a risk. An attacker has an opportunity to remotely exploit any vulnerbility that might be present in the printer: whether due to a bug or a misconfiguration.

Periodically, concerns are published raising the alarm that printers may be used an as attack vector. Yet, real-world examples of publicly disclosed attacks against printers are not common: they do occur but do no seem to match the rhetoric.

We were inspired by a A CyberNews Article explaining how journalists “hijacked 28,000 unsecured printers” The authors of this article scanned common printer ports and used common printer protocols. They identified 800,000 printers accessible over the Internet and 28,000 that had security vulnerabilities. They notified those at risk by printing their own article on how to secure printers.

While the CyberNews authors cited past incidents (1, 2) of mass hacking of printers, we noted that the impact of those incidents was low: offensive text printed with no lasting or severe impact. Yet, the possibility of doing worse is possible.

Do exposed printers really get attacked?

To answer this question, we decided to setup a honeypot and see how often it was attacked and what attackers would choose to do.

This is part 1 of our experiment.

Methods

The honeypot we used was created with miniprint by Dan Salman and we ran it for 36 days in our first attempt.

Miniprint behaves as if it were a vulnerable printer exposed on a public network. Miniprint is written in python and listens on port 9100 for TCP connections. It simulates a printer responding to PJL commands with raw network protocol to communicate.

It supports PJL commands that allow printing and directory traversal, and has a fully functioning file system. These include:

- info status, which returns status of the printer,

- info id, which returns a numerical printer identification,

- echo, which sends a specified message back to the host,

- pjl_command,

- Fsdirlit, which provides a list of directories in the filesystem,

- fsmkdir, which creates a directory

- fsquery, which allows traversal,

- fsupload, which allows for upload of a file,

- ustatusoff, which stops host from recieving job messages,

- and rdymsg which formats the CMS ready message.

Miniprint captures IP’s, strings, and executed commands and logged them. If someone attempts to print a document, miniprint will save a copy of the file sent to the printer.

We created a Digital Ocean Droplet running Ubuntu Linux. Digital Ocean gives us the opportunity to select the geography that we want to run our host in, allowing us to check if some geographies are most likely to be attacked than others.

Amsterdam was selected as a geographical location for our first honeypot.

We occasionally port scanned the honeypot to ensure smooth operation.

Results

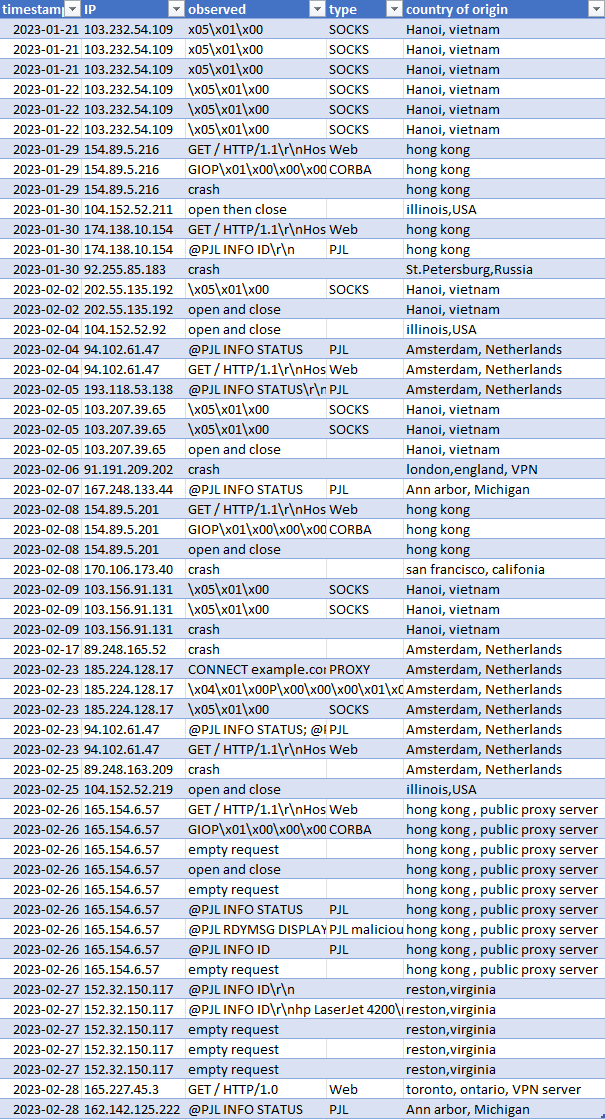

Our results suggest that printers are a neglected attack vector.

We observed few PJL connections, nothing significantly malicious. Noteably, no attempts were made to print anything with the honeypot.

During one month of running our honeypot we found very few connections to our printer. Most connections were obvious scans for open proxies. Some connections were attempting to conned to a CORBA service that also uses Port 9100 as its standard port.

Most of the connections were not PJL (not looking for a printer) and the ones that were PJL typically just checked for the type of printer or it’s status.

Did we see attacks? Any attempts at exploitation or abuse. Yes, but they were insignificant. For example, we saw one attempt to change the honeypot printer’s “Ready Message”: something for which there are widely available scripts, including as part of NMAP.

Timeline of Connections

The following table shows a timeline of all connections to our honeypot along with date, attribution (IP, country, etc), request (truncated), and our interpretation of what the adversary was attempting to do.

Selected Examples

These section each show details of our observations for specific selected examples. Many connections had similar or duplicate observables and we only show a single example in those cases.

CORBA GIOP Scans

We observe TODO N connections that were clearly scanning for CORBA GIOP services.

These scans use general inter-orb (GIOP) protocol. It is used by object request brokers to communicate on a network. We can’t decide conclusively what the first string is for, but we have several guesses. Could this be a NOP sled attempting exploitation of a GIOP service? We think another possibility is more likely. It is possible that the protocol used has fields required. The string may be filling those fields with null strings. We don’t understand CORBA so this is a mystery.

The following strings were captured by the honeypot:

b’GIOP\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00<\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00\x11\x00\x00

x00\x02\x00\x02\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x05\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x04INIT

\x00\x00\x00\x04get\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x0cNameService\x00’

SOCKS5 Proxy Scans

Criminals are constantly looking for open proxies on the Internet. Socks Proxies are particularily popular. You can create them using SSH or other server software. We observed TODO N scans looking for SOCKS 5 proxies. They look like this: \x05\x01\x00

Web Server Scans

Many connections were connecting using HTTP. Perhaps they were attempting to determine if our port was a web server. A typical example is:

GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: 167.99.211.61:9100\r\nAccept: /’

PJL Scans

‘@PJL INFO STATUS\r\nCODE= 10001\r\nDISPLAY=”Ready”\r\nONLINE=True’

@PJL INFO ID\r\nhp LaserJet 4200\r\n\x1b

@PJL RDYMSG DISPLAY = “rdymsgarg”\r\n@PJL INFO STATUS @PJL INFO STATUS\r\nCODE=10001\r\nDISPLAY=”rdymsgarg”\r\nONLINE=True

Discussion

The IP’s gathered were searched using virustotal and reverseDNSlookup. Locations logged include: Amsterdam, Haug, St.petersburg , Hanoi , and Hong Kong. Most of the IP addresses we observed were from data centers, None from ranges we could associate with home networks, cable modems or retail/home Internet service providers.

If miniprint had been a real printer, an attacker would have been completely capable of printing an uploaded file. At its most juvenile, an attacker could use a print job to deplete ink and paper as well as carry out an office prank.

Attackers could have attempted to list file names. Printed file names can themselves reveal sensitive infomation of the contents of the document being printed.

An attacker could have attempted exploitation of vulnerabilities in the software listening on Port 9100. Some printers have vulnerabilities. Presumabily, when an attacker checks the ID of the printer, and gets the model of printer as a response, they have enough to narrow down the exploits they might try. If successfully exploited on port 9100, the attack could use the printer to intercept data or for lateral movement.

We didn’t see any of those attacks.

Limitations

Miniprint was a good starting point, but we noticed that it would frequently crash. There appear to be unhandled exceptions for some types of input. We have not attempted to correct this bug but will attempt to auto-restart it in our next phase of experiments.

During our first month of experiements, we simply checked every day or two and restarted miniprint if it had crashed.

This left us with some gaps in our data collection but we ran the experiment for additional days (36 days instead of 30 days) to compenstate.

Expansion

A next possible step would be to add other honeypots onto the network, to capture lateral movement of an attacker.

Previous printer exploits have been documented, including critical level vulnerabilities. An attacker may search for a specific vulnerable model before launching an attack. Another possible setup would be to create multiple honeypots, with a randomized list of different printers.

These could be commonly used printers or printers with critical level exploits. Printer-specific results may be more likely.

An example of this would be CVE-2022-3942. This is a critical level vulnerability that allows for remote cross site scripting. This is caused by unknown processing php-sms/?p=request_quote in the sourceCodester Sanitization Management System. Models affected include LaserJet Pro, Pagewide Pro, OfficeJet, Enterprise, Large Format, and DeskJet.

References

- https://github.com/sa7mon/miniprint

-

https://cybernews.com/security/we-hacked-28000-unsecured-printers-to-raise-awareness-of-printer-security-issues/

- https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2022-3942.

- https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/hundreds-of-hp-printer-models-vulnerable-to-remote-code-execution/

The Cybersecurity Librarian

The Cybersecurity Librarian